Story

Scientists awarded £2.6million to examine environmental impacts of biodegradable plastics

24 November 2020

To address that, a team of UK scientists has been awarded £2.6million for a four-year project assessing how these materials break down and, in turn, whether the plastics or their breakdown products affect species both on land and in the marine environment.

BIO-PLASTIC-RISK is being supported by a grant from the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC), part of UK Research and Innovation. It is being led by researchers at the University of Plymouth working alongside colleagues at the University of Bath and Plymouth Marine Laboratory.

The project brings together a team of marine and terrestrial biologists, material and polymer scientists, and ecotoxicologists, and will expand on extensive previous research by the partners into the causes and effects of microplastic pollution.

Among its key objectives will be to develop a better understanding of biodegradable materials, how they react on entering the environment, and how their characteristics can be tailored to minimise any potential risks. It will also explore any effects the chemicals added to the plastics might have on organisms, how that in turn affects wider ecosystems and whether certain parts of our environment are more at risk than others.

In addition to the academic involvement, the project partners include representatives from the global textiles and packaging industry, and an advisory group representing Government agencies, biodegradable bioplastics producers, commercial users, water authorities and NGOs.

Researchers believe the project will ultimately also be of interest to sustainability experts and social scientists, helping to guide understanding about any positive effects biodegradable materials can have for the circular economy and to inform behaviour change initiatives in relation to packaging choices and disposal.

Professor Richard Thompson OBE FRS, Head of the International Marine Litter Research Unit at the University of Plymouth, is Principal Investigator on the project. His team previously coordinated research which showed that biodegradable bags can hold a full load of shopping three years after being discarded in the environment.

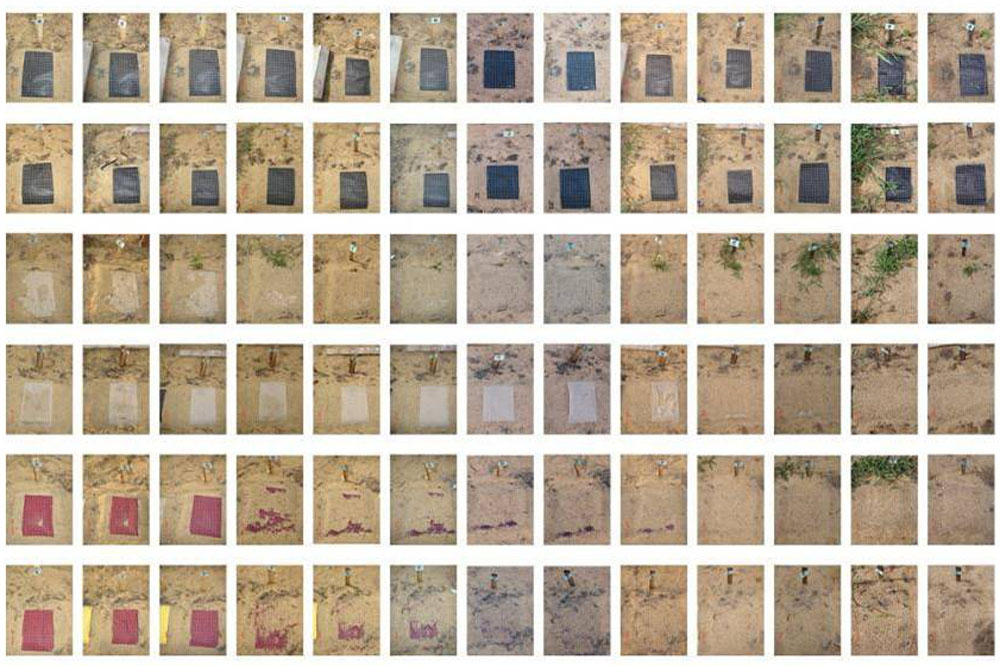

He said: “This is a truly ground-breaking project. For years, biodegradable materials – including plant-based bioplastics – have been highlighted for their potential to reduce the environmental impact of packaging waste. However, there hasn’t been the detailed research to identify precisely how that might be achieved. Through this project, we hope to establish, in the open environment as opposed to managed waste systems, what works and what doesn’t, in terms of the materials’ characteristics and effects. But we can also explore how best to bring about the changes required to move from our throwaway society and help maximise the benefits of plastics without the current levels of largely unintended environmental and economic impacts.”

Professor Pennie Lindeque, Head of Science for Marine Ecology and Biodiversity at Plymouth Marine Laboratory, said: “Biodegradable materials have the potential to provide an alternative to traditional plastics, thereby helping to reduce the impacts of plastic waste. However, we must be sure that such materials – biodegradable bioplastics (BBPs) – and the chemicals they contain, do in fact demonstrate little or no impact on organisms and ecosystems. At PML, we will contribute to this project by establishing the potential toxicity of BBP fragments and chemical additives, as well as determining the interaction of BBPs with ecological and biogeochemical process, in the marine environment.”

Dr Antoine Buchard, Reader in Chemistry within the University of Bath’s Centre for Sustainable and Circular Technologies and a Royal Society University Research Fellow, added: “We use plastics because they can do things that other materials cannot. But because of misguided utilisation, their environmental impact has been overshadowing their benefits. The solution is not to ban plastics altogether: there is rather an opportunity to redesign plastics and how we use them. The reliance of plastics on dwindling fossil fuels is real, and bioplastics, those derived from renewable feedstocks such as plants, are part of the solution to make plastics sustainable. With circular economy concepts in mind, while recycling and reuse of bioplastics need to be maximised, we cannot ignore that some will leak in the environment, in particular the seas, so it is important to understand how they can be designed, at the molecular level, to not have any negative impact on the environment, while remaining fit for purpose.”