Story

Discovering hidden ocean life in one of the UK’s most remote Overseas Territories

19 November 2025

Professor Kerry Howell is currently in Ascension Island – an isolated volcanic island in the South Atlantic, and one of the UK’s most remote Overseas Territories – leading the next stage of research to explore the island’s hidden ecosystems.

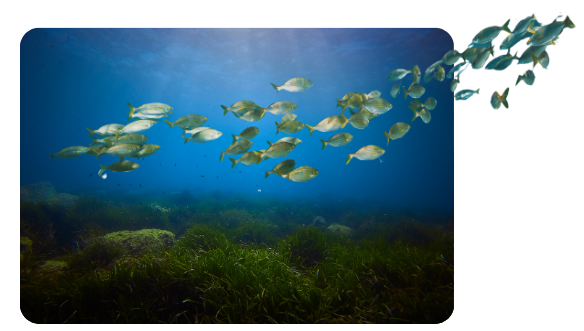

Image: Mesophotic ocean life found in the Ascension Island Marine Protected Area, photographed by members of the DPlus213 funded project during fieldwork from this project last year. Image credit: DPlus213 project.

One year on from her last fieldwork trip, Professor Kerry Howell has returned to Ascension Island to continue vital research on its mesophotic* ecosystems, found between 30 and 200 metres below the surface.

* The term ‘Mesophotic’ originates from the Latin word meso (meaning middle) and photic (meaning light). Mesophotic ecosystems are typically between 30 and 150 meters (approximately 100 to 500 feet) deep, where light levels are low but still sufficient for some photosynthesis.

The project is helping to build the first-ever baseline understanding of these deeper habitats, that will support the Ascension Island Government to effectively manage fisheries, quantify carbon sequestration and assess threats to the Marine Protected Area (MPA).

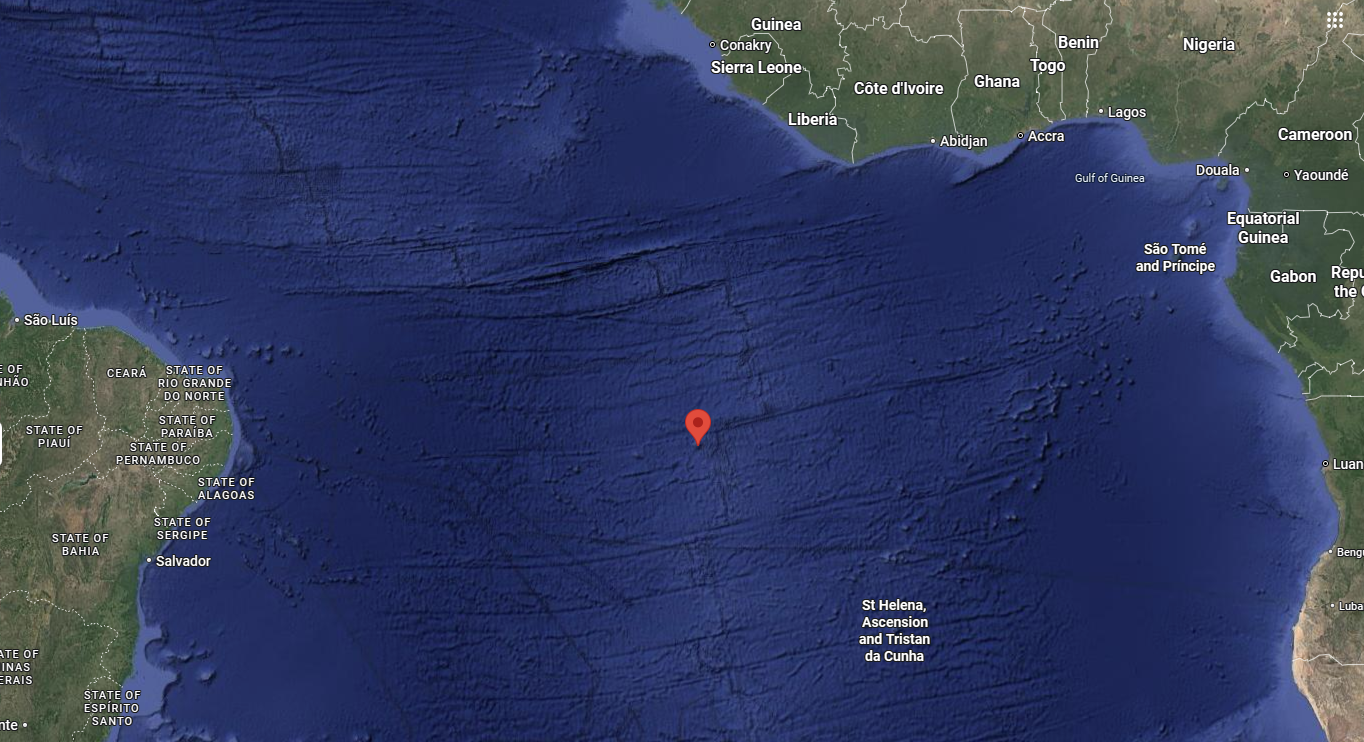

Image: Ascension Island – located by the red pin – is about 960 miles (1,540 km) from the coast of Africa and 1,400 miles (2,300 km) from the coast of South America. It is governed as part of the British Overseas Territory of Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha, of which the main island, Saint Helena, is around 800 miles (1,300 km) to the southeast.

Professor Howell explains why the mesophotic zone remains one of the least explored regions of the ocean:

“In most places across the world, knowledge stops at a depth of about 30 metres, because that’s the limit of most recreational diving. And then, past this depth, there’s no real understanding of what is out there.”

To help fill this gap for Ascension Island, Kerry and her team are deploying low-cost underwater camera systems from small research boats. These devices drift gently with the currents, capturing video footage of life on the seabed without causing any disturbance.

Image: Kerry’s team dropping the low-cost camera systems from the RIB. Image credit: Prof Kerry Howell.

Reaching depths of up to 200 metres – far beyond typical diving limits – the cameras are opening a window into a crucial but often overlooked part of the ocean, where scientific understanding has traditionally stopped at around 30 metres.

“It’s a non-invasive form of sampling – the equivalent would be trawling, but this is just using cameras to have a look at the animals that live there,” explained Professor Howell.

“Not only that, but the equipment we’re using is really low-cost, and can also be deployed from a very small boat. That kind of gives opportunities to other nations who might need small-boat solutions. It’s ideal for island nations.”

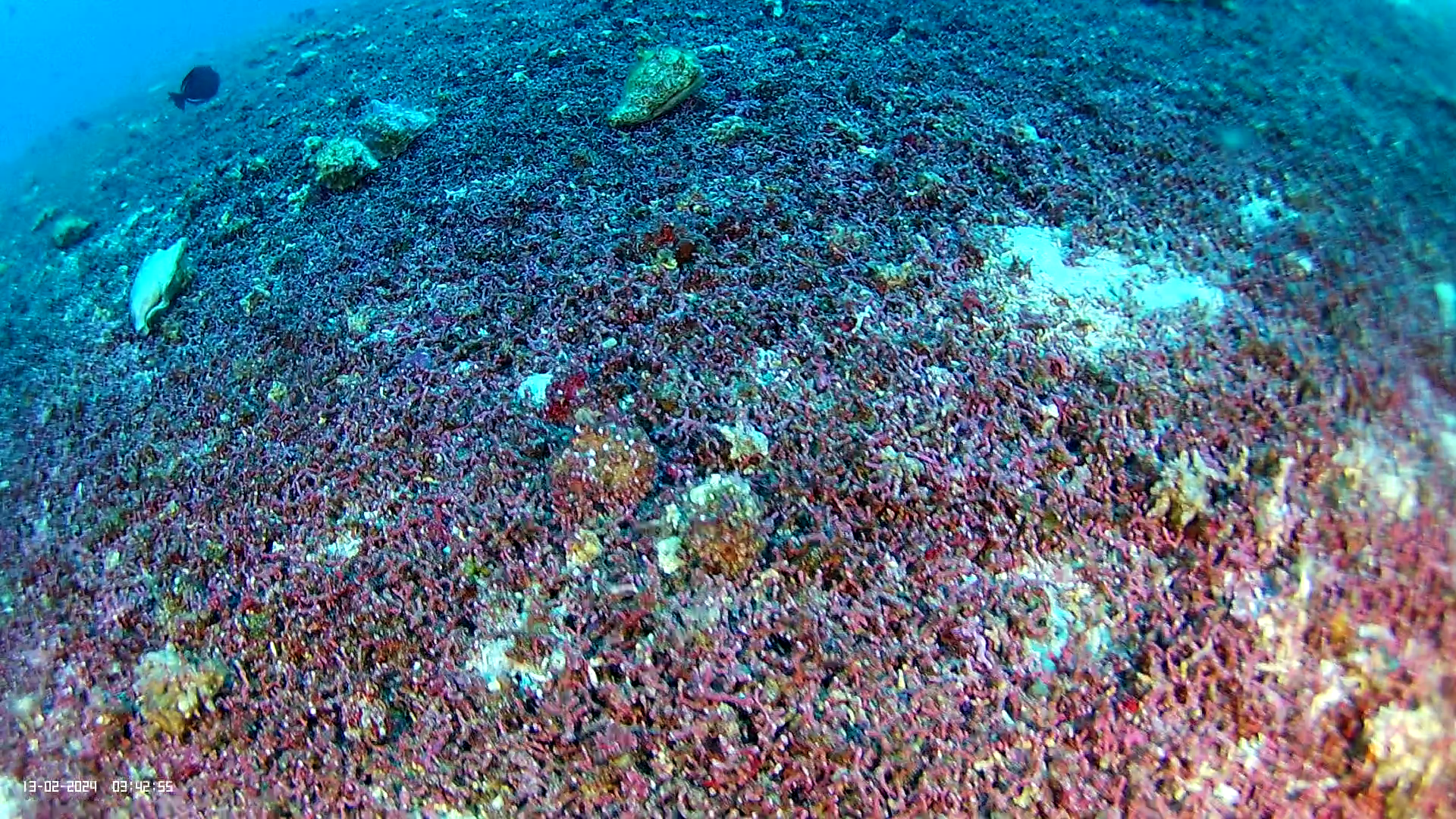

Image: Stills from camera footage taken at Ascension Island last year. Image credit: DPlus213 project.

The current visit will test and refine habitat maps created from the team’s first expedition, in December last year.

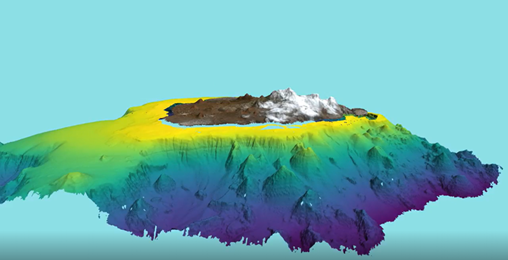

“This second visit is different to the first. Last year, we created some maps that have identified linkages with what sorts of habitats are typically found in what areas. The British Geological Survey mapped the bathymetry – that is seafloor landscape – of Ascension Island acoustically. And then, referring to that underwater map, we interpret what habitats and animals can be seen in the video into substrate-type lists – of what we’ve seen and where – in addition to location-specific temperature and salinity data.”

Image: The British Geological Survey created an acoustic underwater map of the bathymetry of Ascension Island, to which Kerry and the team can apply data from what is seen on the cameras in addition to temperature and salinity data.

“And so, we can take all that environmental data, and the information about the communities that we’ve seen, and then we can make a model that looks at the conditions under which those communities occur, the environmental conditions, so the temperature range, the salinity range. And then and then we can use that in a model to predict where else we should find those different communities, and that’s what makes the map.”

“This year, we’re going to go and have a look in places we haven’t looked, and see if our maps are actually telling us the right thing. We’re going to look in places where our map says, ‘oh, there should be X here, or Y there’. And then, whatever data we collect this time, even if we find our maps are not correct – which we invariably will find they’re not – all of that new information we can then take to improve and refine the model.”

Image: Prof Howell on the RIB with colleagues

The trip will also bring together scientists from additional UK Overseas Territories (UKOTs) Bermuda and St Helena for the first time, for a hands-on knowledge exchange – sharing methods, tools and experiences with the goal of replicating similar surveys across multiple Atlantic islands.

“We’re going to spend time talking and sharing knowledge of how to survey these systems, this will include deploying the cameras, and then talking about whether something like that might be doable in their region too, with the intention of drafting a research proposal to replicate a similar type of study in these territories.”

“The great thing about Bermuda, Ascension, and St. Helena is that they span quite a big latitudinal gradient – if we can replicate this research on all three islands, and pull that data together, it will tell us something much bigger about these largely unexplored oceanic islands – all of which are in the Atlantic,” she explains.

“So, each is a piece of a much bigger puzzle.”

All findings from the project will feed directly into local management of the MPA and fisheries.

“So, the Ascension Island Government were there from the very start – they wrote the proposal with us, and their aim is to better understand the ecosystems within the MPA, because Ascension Island is a massive MPA.”

The project, funded by the DEFRA Darwin Initiative, and titled, ‘Building baseline knowledge of mesophotic* ecosystems in Ascension Island MPA’, is a collaboration between the Ascension Island Government, Plymouth Marine Laboratory and the University of Plymouth.

“It’s great that this fund exists and it’s enabled us to learn about a part of UK territory that we just basically otherwise would have no clue about,” said Professor Howell.

“There are few mechanisms to fund Overseas Territory work, because they don’t count as international but they’re not part of the mainland UK either – so the Darwin Initiative has been essential.”

The project runs until March 2026, when the team will bring together their findings into updated maps and models to support conservation planning.

Looking ahead, Professor Howell, the Ascension Island Government, and colleagues are also bidding for new research ship time, which could take this work even deeper – into the uncharted abyssal habitats surrounding Ascension.

“If we’re successful in our bid we could be investigating much deeper habitats with a remotely operated vehicle,” said Professor Howell.

Asked whether her team might discover new species in the waters, Kerry said:

“That one would let us take samples – so watch this space!”

Related information

About the Ascension Island Marine Protected Area…

‘In 2019, Ascension Island’s entire 445,000km2 marine zone was declared a Marine Protected Area (MPA), where no large-scale commercial fishing or seabed mining is permitted. This makes the Ascension Island MPA one of the largest areas of highly protected ocean in the world.

It supports many species that are found nowhere else on earth, deep sea and open ocean habitats that remain largely untouched and unexplored, and thousands of nesting turtles and seabirds that take advantage of a speck of dry land in the middle of the Atlantic. The MPA seeks to protect all of these and the natural processes that sustain them.’

[Source: Ascension Island Marine Protected Area]

About Professor Howell

Kerry Howell is Professor of deep-sea ecology at the Plymouth Marine Laboratory and the University of Plymouth. She is the Ocean Challenge Lead for Biodiversity at PML.