Story

WATCH NOW: Real-time imaging of microplastic gut passage in zooplankton

05 January 2026

A new study has, for the first time, recorded and measured just how fast microplastics move through the gut passage of a key group of zooplankton in real time – and used those measurements to estimate how much plastic these tiny animals might be transporting – and sinking down – through the ocean each day.

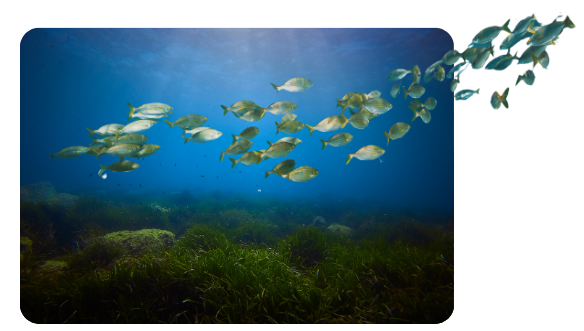

Zooplankton are already emerging as a major biological pathway for microplastics to transport through marine ecosystems. With over 125 trillion microplastic particles estimated to have accumulated in the ocean, understanding how these pollutants are moving through marine ecosystems and food webs is vital for predicting long-term consequences for ocean health.

Copepods are widely considered to be the most numerous zooplankton in our ocean, dominating zooplankton communities in nearly every ocean region, from surface waters to the deep sea. Their staggering numbers mean that even small actions by individual animals – like ingesting microplastics – can collectively drive substantial ecosystem-level changes.

New research, authored by Dr Valentina Fagiano (Oceanographic Centre of the Balearic Islands, COB-IEO-CSIC) and PML’s Dr Matthew Cole, Dr Rachel Coppock and Professor Penelope Lindeque, reveals that copepods may be transporting hundreds of microplastic particles per cubic metre of seawater down through the water column each and every day.

The paper, ‘Real-time visualization reveals copepod mediated microplastic flux’, published in Journal of Hazardous Materials, provides one of the clearest quantitative pictures to date of how microplastics are cycled by zooplankton in the ocean.

WATCH NOW: Real-time imaging of microplastic gut passage in zooplankton

Zooplankton, and copepods in particular, are central to the marine food web. They eat microalgae and are, in turn, eaten by fish, seabirds and marine mammals. They also drive the ‘biological pump’, packaging carbon into faecal pellets that sink into deeper waters.

In recent years, copepods have also been recognised as vectors for microplastics – ingesting tiny plastic particles suspended in seawater and potentially passing them on to predators, or exporting them to depth via their pellets and carcasses. But until now, there has been no precise way to gauge how much plastic an individual copepod processes and how fast.

Through the study, researchers collected the copepods Calanus helgolandicus (a common North Atlantic copepod) through a fine-mesh plankton net, at the L4 Station of Western Channel Observatory – about six nautical miles south of Plymouth – aboard PML’s Research Vessel Quest.

In the lab, the copepods were exposed to three common types of microplastics:

- fluorescent polystyrene beads

- polyamide (Nylon) fibres

- polyamide (Nylon) fragments

These were offered under different food conditions, allowing the scientists to test whether plastic shape or food availability changed how quickly particles moved through the gut.

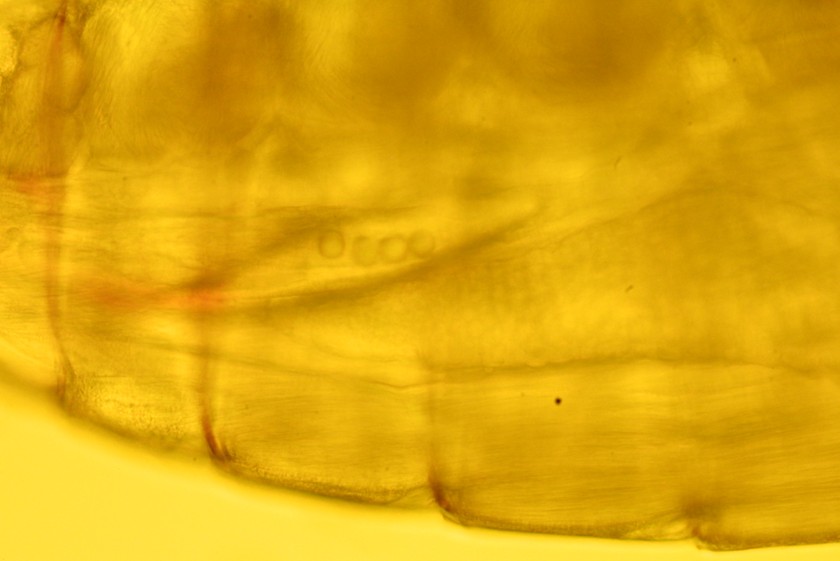

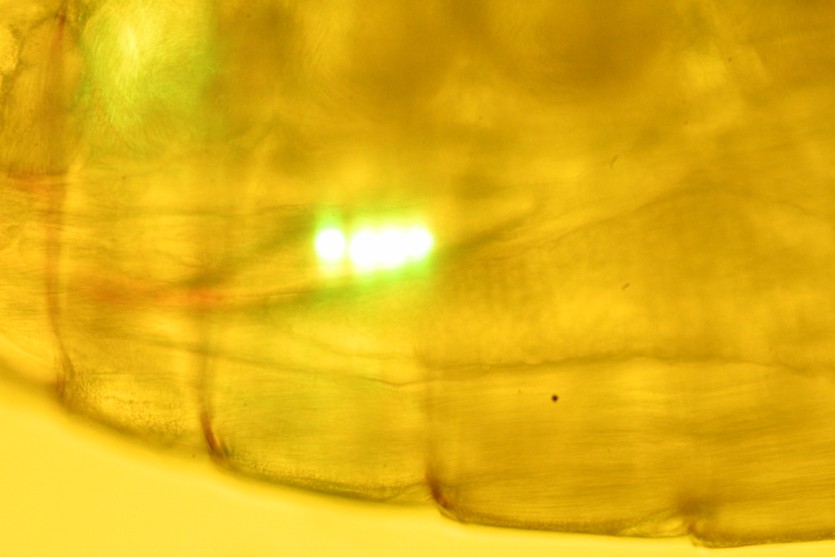

Images below: Microplastic beads seen in the central tube of a copepod [their intestinal tract], as evidenced here, fluorescently labelled beads help with visualisation and identification.

Using real-time visualisation, the researchers tracked individual microplastic particles as they were ingested and later expelled. This allowed them to measure two key metrics with high precision:

- Gut passage time – how long a microplastic particle stays inside the copepod

- Ingestion interval – how often a new plastic particle is consumed

Across all experiments, gut passage times clustered around a median of roughly 40 minutes, and were consistent across plastic shapes and food concentrations. In other words: beads, fibres and fragments all moved through the gut at similar speeds, and feeding conditions did not significantly slow or accelerate plastic throughput.

By combining these measurements with realistic estimates of copepod abundance in the western English Channel – one of the most highly studied bodies of water in the world – the team calculated that copepods could be driving microplastic fluxes on the order of about 271 particles per cubic metre of seawater per day, in that region.

Senior marine ecologist and ecotoxicologist at PML, Dr Matthew Cole, explains how copepods sink microplastics after ingestion:

“Copepod faecal pellets are negatively buoyant – meaning they sink down the water column – and so, when microplastics have been ingested by copepods, and then repackaged into the faecal pellets, the microplastics should drop down the water column with them.”

Dr Rachel Coppock, Marine Ecologist at PML, added:

“Microplastic pollution is often framed as a surface ocean problem, but our study shows that zooplankton are constantly moving plastics through the water column, and into the food web. Copepods don’t just encounter microplastics – they process and transport them, day in, day out.”

Professor Penelope Lindeque outlines the wider implications:

“I would liken this process to both a microplastic plumbing system, and a microplastic food delivery service. Zooplankton are both sinking microplastics down the water column, and passing them higher up in the marine food chain.”

Up to now, many large-scale computer models of microplastic transport have lacked species-specific, process-based parameters for zooplankton ingestion and egestion. The quantitative framework developed here – based on gut passage times, ingestion intervals and realistic abundances – offers a way to:

- Integrate zooplankton behaviour into ocean plastic transport models

- Reduce uncertainty around where microplastics accumulate over time

- Improve risk assessments for ecologically or economically important regions

Ultimately, that helps scientists and policymakers identify hotspots of microplastic exposure and potential intervention points.

The study was a collaboration between visiting scientist Dr Valentina Fagiano, based at COB-IEO-CSIC in Spain, and PML’s Dr Matthew Cole, Rachel Coppock and Prof Penelope Lindeque – internationally-recognised leaders in microplastics and plankton ecology.

The partnership combines PML’s expertise in zooplankton ecology and microplastic methods with Valentina’s emerging specialism in real-time visualisation and flux quantification, illustrating the value of sustained international mentoring and training.

Lead author Dr Fagiano, said:

“By quantifying this flux, we can start to link what happens inside a single animal to how plastics are redistributed across entire ecosystems.”

“Our research has shown that zooplankton readily ingest microplastics 24/7. Copepods don’t just encounter microplastics – they are like mini biological pumps, – processing and repackaging the microplastics into their faeces, which sink through the water column and accumulate in underlying sediment.”

“Having realistic numbers for ingestion and gut passage is a vital for computer models. It means we can better predict where microplastics end up, which species are most exposed, and how this pollution interacts with other pressures on marine ecosystems.”

Related information

Full paper: Real-time visualization reveals copepod mediated microplastic flux

This research was funded by the UK Natural Environment Research Council through its National Capability Long-term Single Centre Science Programme, Atlantic Climate and Environment Strategic Science (AtlantiS).

Dr Fagiano’s research stay was partially financed through a predoctoral fellowship (FPI–CAIB), co-financed by the Government of the Balearic Islands and the European Social Fund, as well as through a mobility grant funded by the Government of the Balearic Islands.