Story

“Record-Breaking” North Atlantic ocean temperatures: PML Scientists Respond

04 August 2023

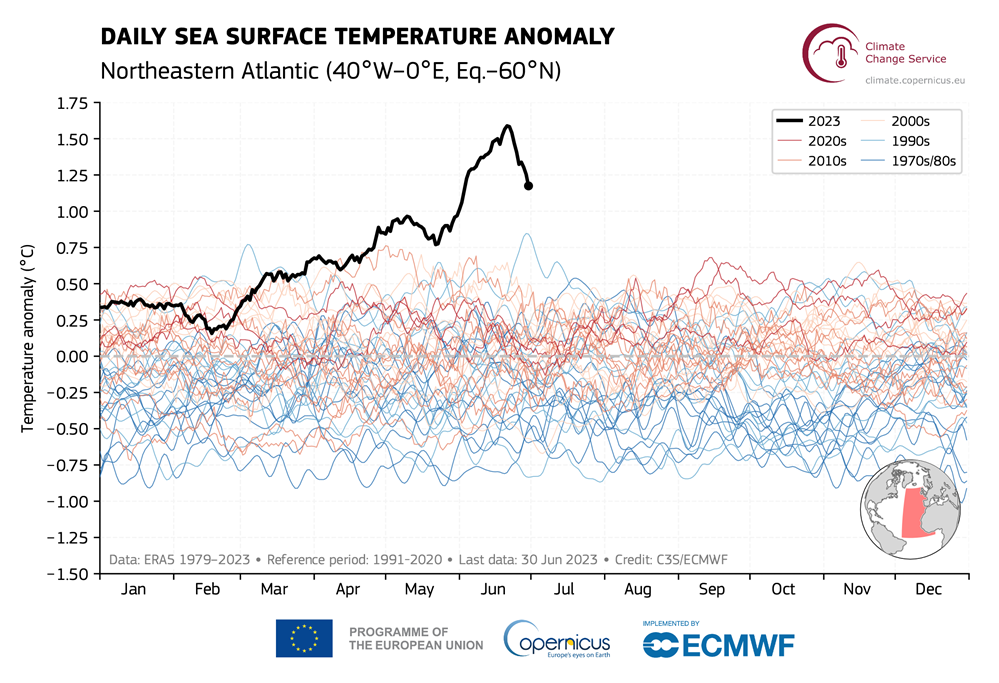

Global average sea surface temperatures reached “unprecedented levels” for June, according to Copernicus (EU’s Earth Observation programme)

PML scientists have been featured in widespread media coverage in the UK and internationally, giving their responses to newly-published data showing “record-breaking” rises in sea temperatures during May and June 2023.

The EU’s Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) routinely publishes monthly climate bulletins reporting on the changes observed in global surface air temperature, sea ice cover and hydrological variables. All the reported findings are based on computer-generated analyses using billions of measurements from satellites, ships, aircraft and weather stations around the world.

According to Copernicus, during May 2023, “sea surface temperatures globally were higher than any previous May, a trend that continued through June, with the global ocean seeing higher sea surface temperatures than any previous June on record”.

Their key findings included:

- Global ocean saw higher sea surface temperatures than any previous June on record

- Exceptionally warm sea surface temperature anomalies were recorded in the north Atlantic, caused by a combination of short-term anomalous circulation in the atmosphere and longer-term changes in the ocean

- Extreme marine heatwaves were observed around Ireland, the U.K. and in the Baltic Sea

- The El Niño continued to strengthen over the tropical eastern Pacific.

Speaking to the BBC, Dr Matt Frost highlighted the way in which rising sea temperature, as a result of climate change, is compounding the many other stressors impacting on the health of the marine environment such as pollution and overfishing, noting that “We are putting oceans under more stress than we have done at any point in history.”

Professor Helen Findlay, Biological Oceanographer, said:

“Temperature is hugely important in regulating biological processes, especially in the ocean where many creatures cannot regulate their own body temperature. These processes impact how species grow, develop, reproduce and interact to make up a healthy ecosystem. As we see more frequent and longer marine heatwaves and overall increases in ocean temperature, some species will be able to cope and some won’t. At an ecosystem level we are still trying to work out what these changes mean – as one species replacing another may seem ok but they can have subtle differences in their life history, which can alter how the ecosystem functions.

“From an initial review, both Copernicus and NOAA data methods are robust and have been used consistently to assess sea surface temperatures over time, both show remarkably similar results, if a fraction of a degree off. The daily “wiggles” will never match because of the subtle differences in the calculations/interpolations/reanalysis. What’s more important is the monthly and yearly patterns: continued year-on-year warming, and to me, what’s so unusual about this second, summer, warming peak that the ocean is experiencing, is that it is much higher than expected for July/August. Data, both NOAA and Copernicus, suggest warmest peaks in March/April before dropping about 0.2 C down to the second lower peak in August. This year, that’s not happened, the second peak appears as big as the first.”

Prof. Tim Smyth being interviewed by the BBC’s Climate Editor Justin Rowlatt

Professor Tim Smyth, Head of Science for Marine Biogeochemistry and Observations said the findings highlighted the importance of long-term monitoring:

“The data we have generated as part of the Western Channel Observatory, providing one of the longest, continuous in situ marine datasets in the world, shows that we are seeing a gradual 0.3 degree per decade increase since the 1960s and that we had a sudden jump in the temperatures in late June, which has since disappeared. We need long-term datasets such as the WCO to be maintained at the frequency at which we are currently sampling – then the marine science community can work together to uncover what the implications are for all of this in the marine environment, and ultimately society.”

Professor Ana M Queirós, Senior Marine and Climate Change Ecologist, said on the BBC World Service:

“In the UK we’re very fortunate to have long-term time series that allow us to look at how species are responding to climate change. Even very locally in Plymouth, we’re seeing changes all across the food web, from zooplankton all the way to fish.”

“We have to think of climate change as not as one process but rather as a process that’s happening all around the globe with different speeds and magnitudes. It’s about primarily temperature but it’s also about other ocean conditions, for example the amount of oxygen is also reducing because of warming temperatures, more CO2 is causing ocean acidification, so it’s a number of processes happening all at the same time. In some areas those changes are faster than others and those regional differences around the globe are to do with ocean circulation patterns and atmospheric processes, and it is the shift in those structures over space and time that causes particular areas to be more sensitive or experience faster climate change than others. We tend to think of these as climate change ‘hotspots’ as opposed to climate change ‘refugia’, where climate change will be more moderate in the short- and mid-term, or climate change ‘hope spots’, where biodiversity may remain more or less as it is now.”

Transcript of live interview with Dr Matt Frost on Deutsche Welle:

Transcript of live interview with Dr Matt Frost on Deutsche Welle:

So why are the oceans so hot right now?

I think there are a number of factors. We can look at some of the immediate factors, such as marine heat waves, which seem to be occurring in all parts of our ocean and in addition, you’ve got things like the world moving towards an El Nino phase, which is a natural event but it’s where the world is warmer in parts because the water is warmer.

I think the important thing to say is that this is what we would expect to see on the back of decades of rising temperatures overall.

So you bring all of those factors together and it’s not a massive surprise that we’re seeing the sort of temperatures we’re seeing and the recipe for disaster of sorts. What could the consequences be for marine life?

It ranges depending on the marine life itself. Some marine life is going to be very vulnerable. So, for example, most people are familiar with things like coral bleaching. They are vulnerable because coral reefs can’t move. If the water gets warmer, they’re just stuck there and once they can’t cope, there is an impact. A lot of species and a lot of the marine life in the ocean can’t do anything. It can’t move so the impacts can potentially be devastating.

When you talk about what we would refer to as mobile species, the whales, the fish, the sea birds and other things, they’re able to move around. But of course, that is also impacting the ecosystem as a whole because their moving around is altering the whole food web.

The oceans are crucial in regulating temperatures around the globe. So how do rising sea temperatures affect the ocean’s ability to do that?

In a range of ways. The main thing is that the ocean takes up most of the heat from carbon dioxide that has been produced and a lot of the greenhouse gases that we’ve been pumping out into the atmosphere. The reason we haven’t seen so much drastic change, is simply it’s been absorbed into the water. As water warms up, it actually can absorb less gas so that has two consequences. One is it holds less oxygen overall but also it doesn’t take up as much carbon dioxide.

So we’re starting to get to the stage where there’s a lot of concern that where the ocean has been sort of our heat regulator, almost like a sort of global air conditioning system, if you like, as it’s keeping us cooler than we should be, that is stopping to happen. Basically, warmer water takes up less gas than cooler water.

Now, one of the particularly vulnerable spots on the globe are the polar regions and they are severely affected by climate change. What impact are high ocean temperatures having here?

Well, they’re being seen very strongly in the polar regions for a number of reasons. One is the polar regions, by definition, they’re cold regions and the species there are adapted to very cold climates. So even small increases in temperature can have massive effects and we’re also seeing things like loss of habitat.

There are iconic images of polar bears trying to find sea ice, that is melting, but there are lots of other species that rely on that. But I think the other thing with the polar regions is that there are a lot of what we call feedback loops. So as the ice melts and then you get less reflectance in terms of the sun and there’s all these quite complex interactions that are going on.

So what we’re actually seeing is the impacts in the polar region are more severe, or more obvious is another way of putting it, than they are in other parts of the world.

Is there any way you see temperatures returning to normal in the oceans?

The issue we have at the moment is the time lag so there isn’t a quick fix. Even if we stopped everything we’re doing now, if we stopped using fossil fuels tomorrow, there would still be a long time lag in terms of seeing the effect of that.

So what most people are hoping is that yes, we can stop, reduce fossil fuel use and all the other things that are causing the problem. But the two things we need to do really is we need to adapt, so we need to just accept that at least for some decades to come, we’re going to be living with these high temperatures. That means the way we fish, the way we put in marine protected areas and lots of other things all needs to take that into account.

And then there’s the whole mitigation side. There are calls worldwide now for people to stop doing what we’re doing and get a grip on it because we’ve still got a chance to limit the temperature rise to 1.5, 2, 2.5 degrees but if we carry on as we are, we might be looking at a 4 degree rise and that would be completely catastrophic.

So the answer to your question is no, we can’t get everything back to normal straight away, but we could at least limit the severity of the rises we’re facing.

Related information

Related media coverage:

Ocean heat record broken, with grim implications for the planet – BBC News

Newshour – World’s oceans hit record high temperatures – BBC Sounds

Today programmme (from 01:49:56, available online until 1st September 2023)

BBC Radio 4 Six O’Clock News (featuring Prof Tim Smyth – available for one year)