Story

Staff spotlight: Professor Kevin J Flynn - Plankton ecophysiologist

26 January 2026

Meet Professor Kevin Flynn, one of our most accomplished scientists at the laboratory, whose experience spans decades and disciplines. Kevin creates computer simulation models of microscopic organisms, that, whilst invisible to the human eye, play a critical role for all life on Earth. These include the microalgal plankton, predators such as copepods and even bacteria and viruses.

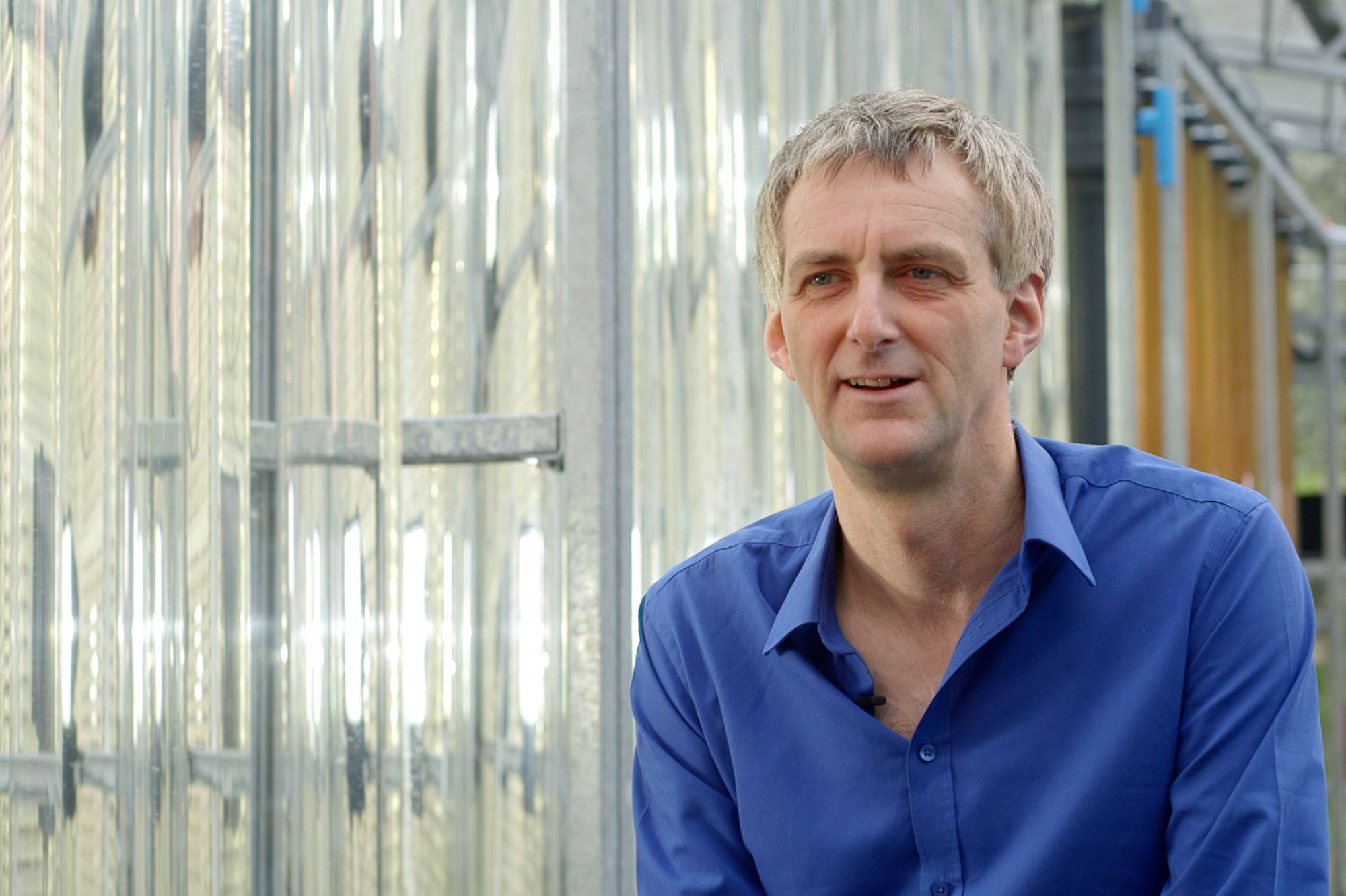

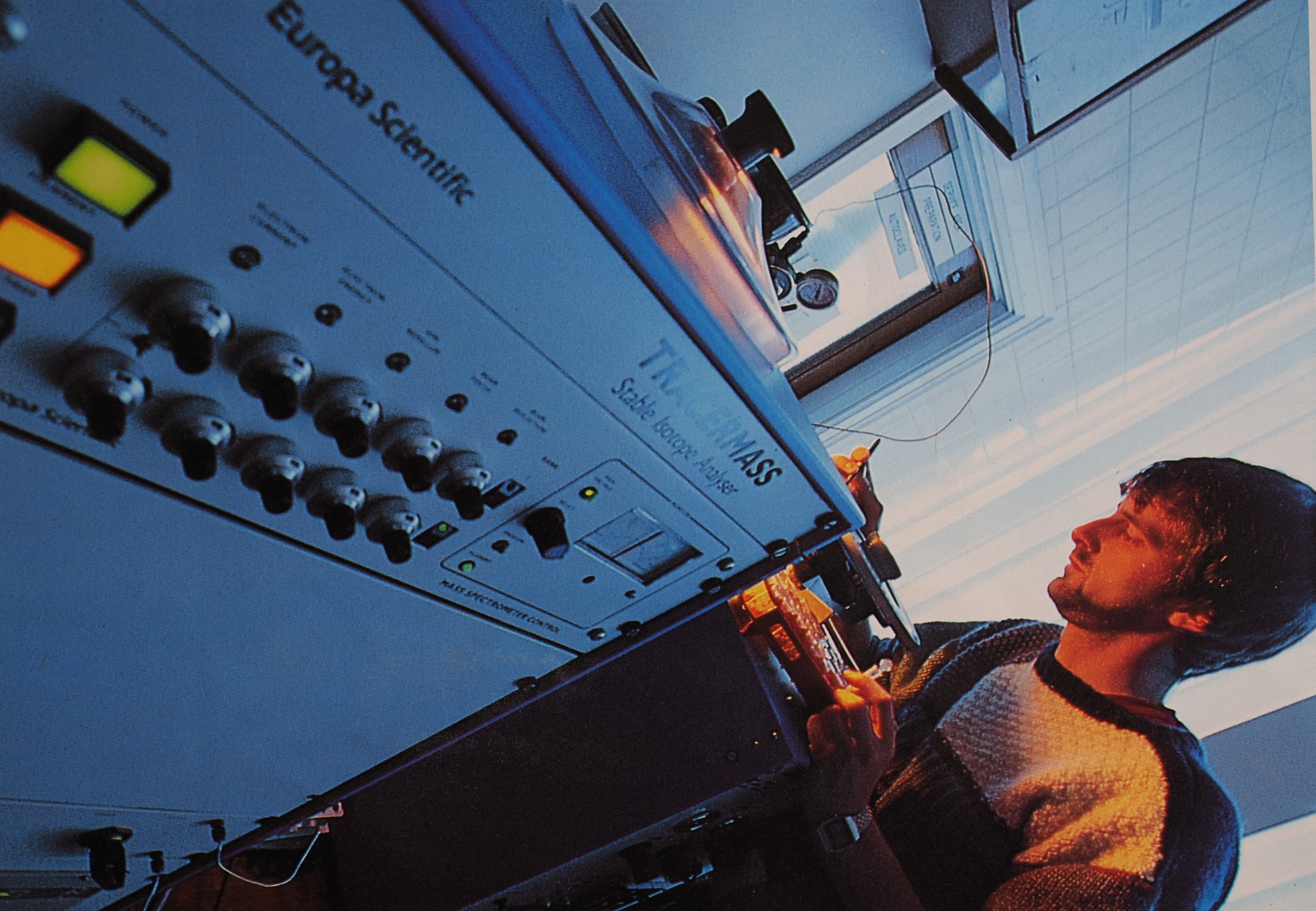

Image caption: Kevin pictured in 2015 next to the then largest microalgal bioreactor in the UK at the CSAR facility in Swansea, during filming of “Panning for green gold” as an output from the EU-funded Enalgae project.

Whilst he currently works on simulation modelling, Kevin originally trained as an algal physiologist. He describes his background and journey: from marine biology undergraduate to a PhD in algal physiology, with his career later progressing to lecturer and Professor, and the inspirational mentors and colleagues who shaped his path along the way.

“I visited the Marine Biological Association (MBA) during my A-levels; I just wrote and asked if I could look around, and my father drove me down from Yeovil (which is where I grew up), and from that visit I decided to do marine biology at university. I turned down a regular biology degree option from Oxford, which did not win me any prizes from my teachers; whether I should have gone there and then later specialised is a moot point, but the whole system is different now. At that time, marine biology was only available at four universities, and the courses only appealed from Herriot Watt (then still located with ‘Brewing Science’ in Edinburgh while all else had moved to their new campus) and Swansea, which is where I went.”

“My degree at Swansea included a BSc project on light-acclimation in diatoms [Diatoms, a type of phytoplankton, can acclimate their rate of photosynthesis to the rapidly changing light levels in their environment by changing the number of chloroplasts they contain and even moving them around inside the cell], which created a stir because the marine biology degree was run by the ‘Zoology Department’, while the project was in ‘Botany & Microbiology’. The project was supervised by the head of the latter department, Prof Phil Syrett, who had a good-sized team of phytoplankton physiologists.

Image caption: Kevin’s ID photograph from his undergraduate report card. He comments, “My hair would not grow that long again until COVID!”

“Phil subsequently secured a Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) quota PhD studentship for me. That project was on amino acid uptake, then viewed as a source of nitrogen. Of course, now, things having come full circle, we would term that use of amino acids as a form of mixotrophy*.”

[*Mixotrophy is where organisms, such as phytoplankton, can combine phototrophy (where they obtain energy from photosynthesis) with heterotrophy (where they obtain their energy from the metabolism of organic substrates).]

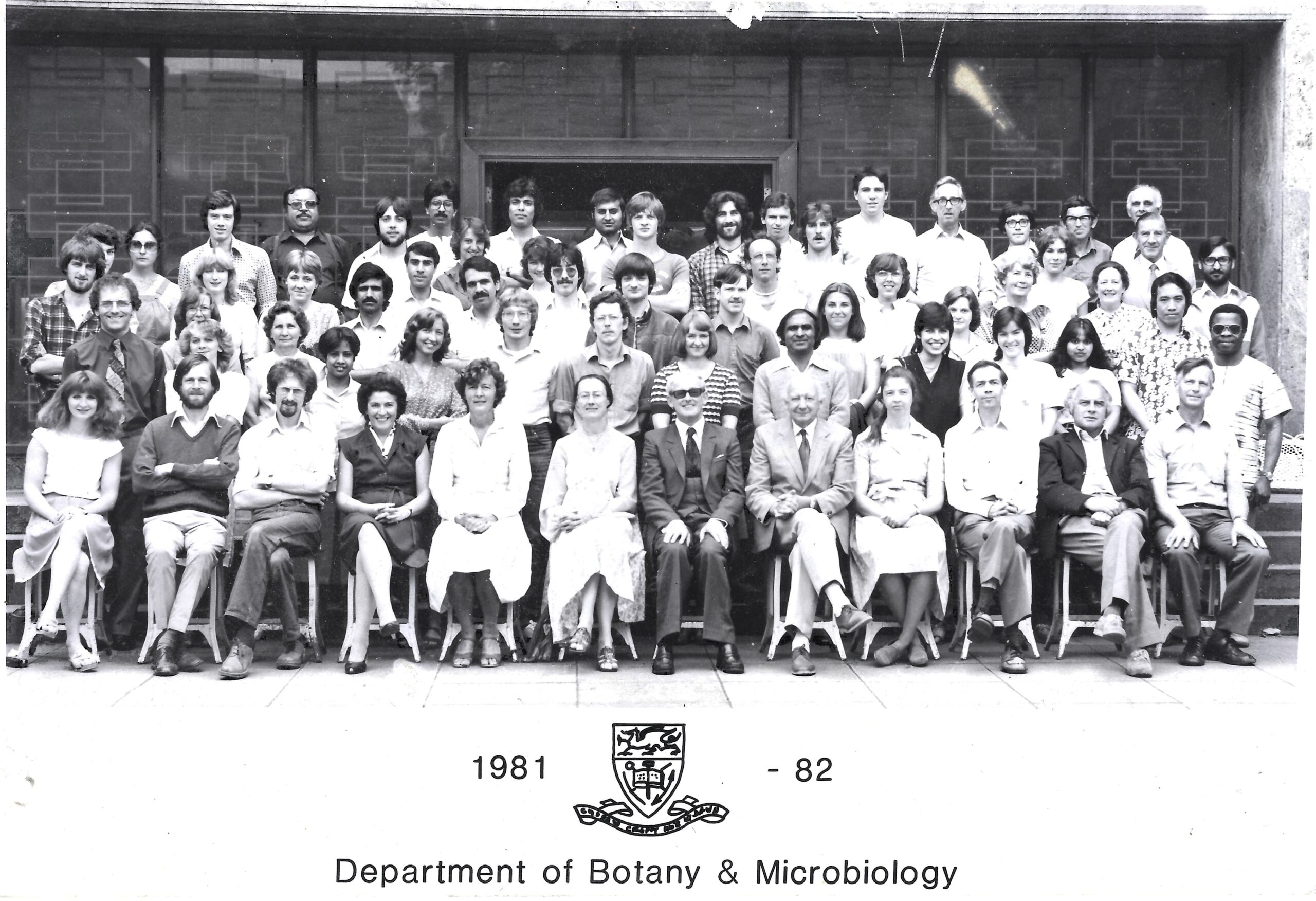

Image caption: From the end of his first PhD year, Kevin is the bearded individual upper far left. Professor Phil Syrett is front row above the number ’82‘. The lady in the front row above-right of ’1981‘ is Dr Helgi Öpik, who was the department’s electron microscopist. Helgi was of a family who escaped from Estonia in the 1940s; her father was the famous astronomer Ernst Öpik, while one of her other relatives is the former MP, Lembit Öpik. Kevin recalls, ”Everyone lived in fear of Helgi who was an authoritarian figure. She was one of my three 1st year UG tutors (yes, three – those were the days!), but over the following decades we became firm friends, and she actually had a very good sense of humour. Proof indeed to never judge a book by its cover.”

“My PhD examiner was one Mr Ian Butler (he hated being called ‘Dr’ as he did not have a PhD), ex-Royal Navy, who was a marine chemist at the Marine Biological Association UK, and a strong proponent of the role of dissolved organic nitrogen and allied topics that we would now see as components of the microbial carbon pump. The PhD viva was ‘interesting’; after the pleasantries and the first 20 minutes of talking about my work, Ian took his bulging briefcase full of his own research papers and ideas, emptied it all over the desk, and said ‘what do you think of this?!’ We spent the rest of the 3 hours of ‘my’ exam with me examining my external examiner’s research. Ian was a great man in my eyes; I miss his humour, his no-nonsense critical foresight, and our discussions.”

“After my PhD, developing from some work I did in the last 6 months, we got a grant from the Science and Engineering Research Council (forerunner of Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC)) to look at the development of nutrient transport proteins. This involved what would now be termed proteomics [the large-scale study of proteins]. It did not work particularly well, but in the interim I applied for a NERC grant, which we got, to develop high-performance liquid chromatography* (HPLC) methods for amino acids [*HPLC is an analytical chemistry technique that separates, identifies, and quantifies components in a mixture]. I applied that analysis not only to external dissolved free amino acids (the official target of the grant) but also to intracellular amino acids; the latter turned out to be really useful as a demonstration of the power of what we would now term metabolomics [the products, intermediates, and substrates of cell metabolism], as a means to track the nutritional status of microalgae. The method is so sensitive that it can readily be used on samples from the field.”

“Indeed, the only time I did ‘proper’ field work was using that methodology. At a fixed station in Bantry Bay (County Cork, Ireland), in conditions so rough that we were dragging the anchor, that idiot Flynn wanted to sample every 2 hours, at several depths, for 24 hrs. The crew came to check that I was OK at various times, which I thought was touching as I was more than slightly green in more ways than one. Later I found out that their concern was slightly tempered by the fact that they were playing cards for money and needed to know whether they would be out for the full 24 hours as that would mean they would get a bonus payment! Anyway, the experiment worked, and secured a nice research paper.”

“Towards the end of that grant, I applied for various post-docs and fellowships, one of which involved an interview at NERC Polaris House for a project on food web dynamics. Another interview was with Professor Mike Fasham FRS of IOS Wormley and Dr Ian Joint of PML, which apparently (according to Mike) was for a position that they were never going to give to me, but they wanted to just have a ‘little chat’! (More on Mike later).”

“The NERC fellowship interview was strange; they liked the project but were not going to send me to the USA to do some of the work in California. They asked where else could I do it? Dunstaffnage Marine Laboratory (DML, Oban, Scotland), was my response. (DML was the lab of the then recently retired Michael Droop, of Droop quota-model fame, who I met on various occasions). And so, I was awarded what turned out to be forerunner of the NERC Advanced Fellowship, before that award category had been properly constituted, and hence I had no consumables budget! Actually, the whole of DML had no consumables budget, because shortly after I was awarded the Fellowship, all the NERC labs were rocked with a financial crisis that eventually saw the demise of DML (it re-emerged as the Scottish Association of Marine Science, SAMS). I was ultimately given a £12k consumable budget for the first year of the Fellowship, an amount of money equal to that for the whole of the remainder of the lab, as I recall.”

“My time at DML was very productive, not least because a 1st year PhD student from Strathclyde University also turned up and wanted to model microalgal growth. That student was Keith Davidson, and we worked as a team for several years. Keith later had his own NERC Fellowship, working at PML. He is now a Professor the Associate Director for Science and Education of SAMS (which occupies the rebuilt DML site at Oban). In passing, 5 of my former PhD students have also worked at PML: Darren Clark, Eurgain John, Nick Stephens, Gemma Cripps (nee Webb) and Suzanna Leles. This time at DML was, though unplanned, the start of a long period of coupled empirical-modelling research. During a subsequent post-doctoral position that Keith had with me he started to use a new piece of software, Powersim Constructor, marketed in the UK by the ElectricBrain Company (one of those names that sticks in your memory). This software was a total revelation for a biologist, set against the alternative of working with Fortran or similar computer code. We could concentrate on modelling the physiology of our planktonic bugs, rather than on debugging computer code.”

“After 1 year at DML, against a backdrop of potential closure or even takeover by the Aberdeen Marine Lab, I left to take up a lectureship in microbiology back at Swansea. My research then went through various periods of harmful algal bloom work (notably with CSIC and IEO at Vigo, Spain), and ammonium-nitrate studies using 15N isotopes to work out how nutrients flowed around the system. It was with the latter that we got a NERC grant for a project with Professor Nick Owens (then at Newcastle University) and Professor Mike Fasham (who had moved with the IOS staff from their former old building in rural Surrey to their newly built National Oceanography Centre (NOC) in Southampton). The idea was for us to do the experiments, and Mike to do the modelling. Very early in that project, however, and learning that I used to write computer games [see below], as well as the existence of Powersim Constructor (now Powersim Studio), Mike declared that I should do the modelling and he would just check that what I was doing made sense.”

Image above: Kevin pictured in 1994 in the algal research laboratory at Swansea loading up samples for elemental and 15N analysis. “This was a publicity photograph for ‘Advances Wales’; normally you wear a lab coat, of course, otherwise I would have been analysing wool!”

“And it was this moment that really pushed my journey into coupling empirical and modelling research. However, the background to all of this, noting that I do not call myself a modeller, stems from when I was doing my PhD. At that time, a certain Sir Clive Sinclair launched a series of home computers: first the ZX80, then the ZX81 (both only with chunky black-and-white video and no sound), and then the colour and sort-of-sound Sinclair Spectrum. It is perhaps difficult to realise the revolution that these computers inspired at the time. The ZX81 was perhaps the first computer that most people in the UK ever used. It had just 1K of RAM (yes, 1K, with a 16K RAM extension available), and plugged into your (black-and-white) TV.”

“A whole industry was set up to exploit these computers, and to get the best out of them you really had to use machine code. So, while waiting for the next cultures of diatoms to grow up for my PhD research, I taught myself Z80 machine code, all entered as hexadecimal with no special programme or debugging tools to help, and with the programmes themselves stored on audio cassette tape. I wrote several computer games, and we sold them via Boots and WH Smith. We did tape-to-tape duplication in our living room, and hand-folded the artwork into the cassette boxes. The bank was convinced that we were doing something with drugs, as they could not understand how we could make so much money from apparently no outlay.”

Image caption: Promotional material for one of Kevin’s games from 1982. That the hero of the movie ‘Tron’ released that same year, was a certain ‘Kevin Flynn’ was of course a total coincidence!

“So, when Mike Fasham poked me into plankton modelling the door was already part opened. However, years of experience of debugging code taught me the advantages of using a platform that enables me to concentrate on getting the biological description right.”

“Mike, like Ian Butler, left an indelible impression on me. Amongst pub talks over Rolls Royce Griffon powered Spitfires and the like, we talked over how plankton modelling needed to develop. This was not that long after the publication of the seminal Fasham et al. Nutrient-Phytoplankton-Zooplankton (NPZ) model, but Mike already wanted to better describe the physiological reality of the plankton. Unhindered by concerns over complexity, he wanted to drop in whatever level of physiological detail my models contained. This was in the late 1990’s – early 2000’s; a quarter of a century ago. One can but wonder what would have happened with the NOC modelling suite if Mike had not retired and then died tragically from prostate cancer only a few years later, and had been able to guide developments.”

“Over the following years, I rose quite rapidly through the university ranks, lecturer, senior-lecturer, Reader. My research work became increasingly wrapped up with developing and deploying models. In 2001, I was awarded a Leverhulme/Royal Society Fellowship, which bought me out of teaching for one year; that enabled me to work full time on models together with Mike Fasham. Other projects subsequently appeared, including a large Carbon Trust funded project on algal biofuels, for which I was contracted to develop the lynchpin model for operating and financially controlling production. With this, shortly later, came the €13 million Enalgae project (led by Robin Shields at Swansea) also on algal biofuels, and then involvement with an EPSRC project on seaweed biofuels (run out of Durham University). From this (and aside from at one point becoming the manager of a seaweed farm moored far too close for comfort next to the Irish Ferry terminal in Milford Haven), we concluded that algal biofuels production was a complete nonstarter from financial and ecological angles. Likewise, it is not going to sequester any significant level of CO2 either.”

“Other projects at Swansea University included a NERC-Defra grant for work on ocean acidification (with PML and Exeter), about which two things stick in my memory. The first is that the home office vet, who had to sanction our fish experiments, just laughed when we told her about the range of pCO2 [Partial pressure of carbon dioxide; pCO2 is a measurement of the amount of carbon dioxide] we were going to use in experiments (because standard aquaculture levels are much, much, higher and cause no problems), though she was concerned with the temperature tests. The other thing is that our much-discussed upper limit of pCO2 selected for those experiments are now, scarily, the atmospheric average.”

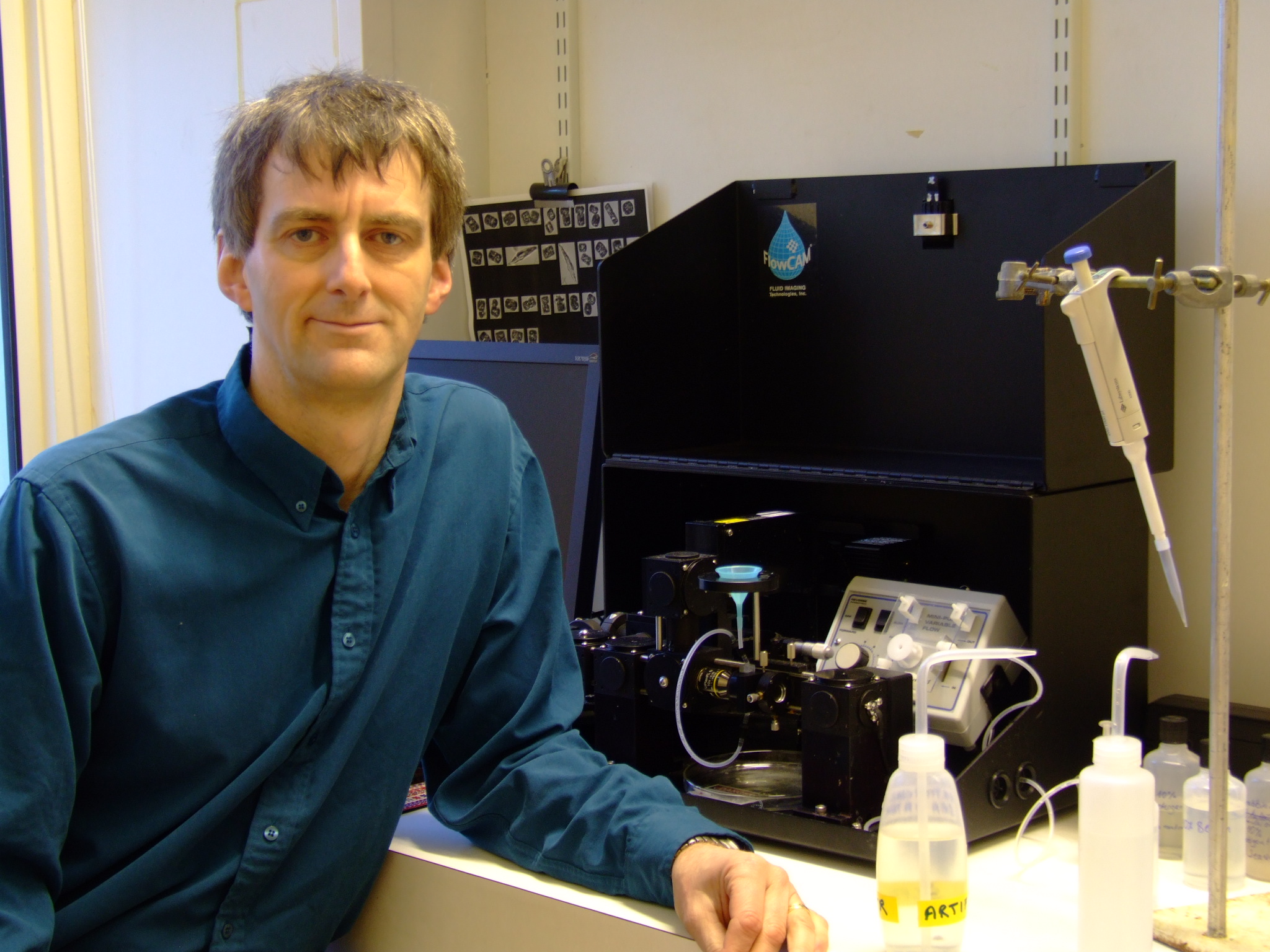

Image caption: Kevin pictured with a new FlowCam in 2009. He says ”Our version was a ‘special‘ which could measure whether the plankton were actually alive! It was used during the ocean acidification projects.”

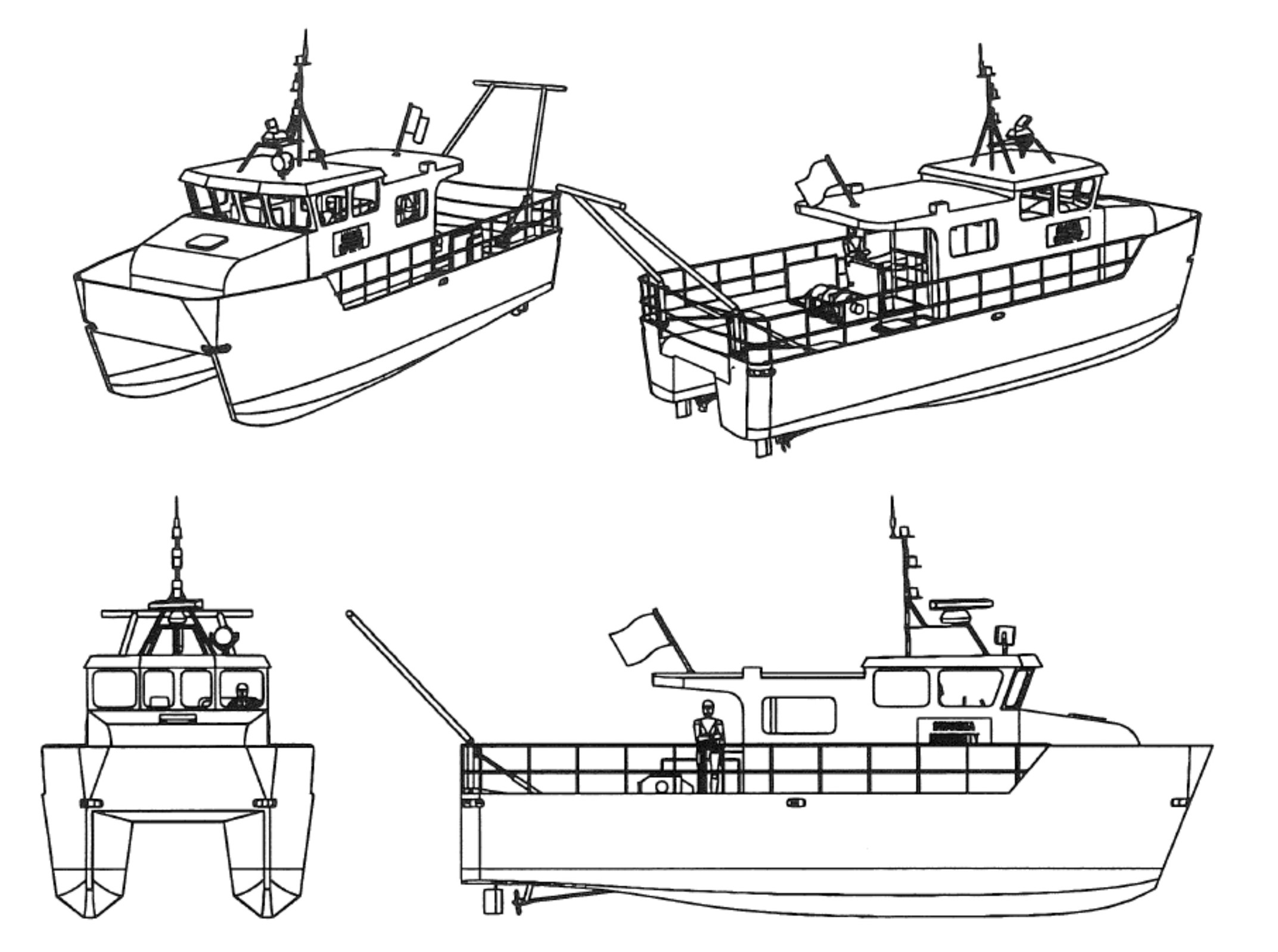

“Oh, and I led a grant application to NERC to purchase a research vessel. This was an aluminium catamaran, complete with a moonpool. Built in Finland, tested in the frozen Baltic with an icebreaker in front of her, she became the first purpose built small research UK vessel of her type. She was named Noctiluca. For naming, I asked for suggestions and then got the staff to vote positively for names they liked, and negatively for those they disliked. Noctiluca was chosen because no one scored that name at all, while the other names all out–competed with each other or were unsuitable as other local boats had similar names. The fact that it was my name suggestion was, of course, a pure fluke (honest), but almost generated a rebellion amongst some staff. Some even claimed that it was unsuitable as the local Coast Guard would not be able to pronounce the word (while apparently being quite capable of pronouncing Greek ship names, written in Greek script). The replacement for Noctiluca at Swansea is a glass-reinforced plastic (GRP) hulled boat; ironic really, as students now go out to study marine biology in a boat made of plastic and which is non-recyclable.”

Image caption: Schematics of the RV Noctiluca, a bespoke design commissioned by Swansea University for research survey and teaching operations in the Bristol Channel. Named after the dinoflagellate, ‘Noctiluca scintillans’ which, in its common form and off the UK coast, is a predator of microalgal blooms. The name Noctiluca scintillans comes from the Latin Noctiluca, meaning “light at night” and scintillans, meaning “shining, throwing out flashes of light”. Blooms of Noctiluca, an organism also commonly referred to as ‘sea-sparkle’, give a blue-light glow to crashing waves at night, or when you paddle through their growths in shallow waters.

“From the early 2000s, an increasing amount of effort was expended on what we now term ‘mixoplankton’, microbes that photosynthesize and eat. From an idea developed by Aditee Mitra, which (dare I say, perhaps inevitably as it was too revolutionary) was rejected for funding by NERC, so we obtained support from the Leverhulme Trust for a series of workshops. These workshops rather set the scene for our modus operandi for developing models, working very closely with those who are experts in the real organisms to ensure the models are conceptually correct, as a sort of Turing Test. Aditee subsequently obtained the largest ever project for working on these organisms, the MixITiN project. PML joined that project when I joined the Lab in 2020 [more below], a project whose key result rewrites a century of phytoplankton-zooplankton dogma. Many of the organisms traditionally called phytoplankton or (protist/micro-) zooplankton are actually mixoplankton; science did not recognise that fact because researchers were not looking for the right combinations of traits or were too resistant to challenging ideas.”

Image caption: Kevin pictured with international colleagues during the Leverhulme-funded mixotroph (now ‘mixoplankton’) project at Rhossilli on the Gower peninsula in 2012. The scientists are (upper photo) Mike Zubkov (formerly PML), Terje Berge, Frede Thingstad, Urban Tillmann, Diane Stoecker, Per J Hansen, Selina Våge, the late great John Raven FRS, and (lower photo) Susane Wilken, Albert Calbet, Edna Granéli, Pat Glibert. Also present is Aditee Mitra and their son Rohan Mitra-Flynn.

Image caption: The 3rd Leverhulme meeting at Horn Point, USA. Amongst those present are John Raven, Gustaaf Hallegraeff, Per J Hansen, JoAnn Burkholder, Bob Sanders, Vivi Pitta, Matt Johnson, Don Schoener, Pat Glibert, George McManus, Fabrice Not, Dave Caron, Diane Stoecker, Hae Jin Jeong (with 2 students), Veronica Lundgren and Todd Kana, plus Aditee’s parents, Aditee and of course Rohan.

“My teaching, across all levels, was originally mainly directed towards process–biotechnology students (microbiology), and then later to marine biology students (plankton). At one point I also taught modelling to all 250 biology students in a non-elective course. Using Powersim Studio, they all coped admirably, and all passed.”

Image caption: As head of department and deputy head of school, Kevin is pictured with colleagues at the undergraduate awards ceremony at Swansea in 2010.

“My other experience in academia includes being deputy head of college/school, head of department and, in the year before resigning from Swansea University, also the joint president of the local branch of the University and College Union. Management experience has included handling the closure of a department of 30+ staff as a consequence of a disastrous REF result under the direction of my predecessor, a suitably horrendous task that had to be hidden from all of my immediate colleagues. Ultimately, the University changed its mind; I needed a new mind.”

“After all that, PML was more than a radical change, but of course both research institute and university go through cycles of growth and cutbacks and changes in direction/emphasis.”

Image caption: The last Leverhulme meeting, in 2014, was for the modelling stakeholders. Kevin on the far right, with PML’s now Chief Executive Professor Icarus Allen the third from right. Also present (middle) are Luca Polimene (then of PML), between Coleen Maloney and Christine Lancelot, with Baris Salihoglu and Tom Anderson (NOC) to the far left.

After such a long time spent at Swansea University, Professor Flynn describes the moment he joined the modelling group at Plymouth Marine Laboratory, which is now our Environmental Intelligence group, and what attracted him to the organisation.

“I joined in April 2020, just as the UK entered COVID lock-down. It was always going to be a remote-working exercise, but not that remote. The role, as I see it, is as a combination of plankton ecology and simulation modelling; asked what I am, I would always headline the response with ‘plankton ecologist’, not as ‘modeller’.”

“The attraction is in many ways longstanding, associated with linkages to Marine Biological Association (MBA) and (what is now) PML dating from the early 1980’s. In a nutshell, the style and range of marine science is the attractor. Arguably, I should have tried to join decades ago.”

Kevin describes how his background in marine biology and ecology has benefited his work in modelling at PML, and details some of the projects he has been working on.

“In the laboratory (DML, Swansea) I had worked on bacteria, various microbial plankton, through to copepods. I have built physiologically-based models of these, and also of viruses. The combination provides a powerful breadth of experience. Ecology requires a holistic understanding which is complex enough at the best of times. Trying to summarise that in a dynamic simulation model shows us as much about what we do not know as what we do know. This can come as an uncomfortable truth to both those who work with empirical science and modelling – working on both, it came as a double shock to me! But, of course, it also indicates where to go next.”

“What I have been working on since joining PML includes wrapping up the microbial carbon pump project (which has yielded some interesting unexpected results that only emerged from modelling the system. We answered a long-standing mystery in marine science: why nitrification only switches ‘on’ under certain conditions – access the paper here), completing the MixITiN project on mixoplankton [mentioned above], modelling virus dynamics (initiated by a brain-wave, for rather obvious reasons, during the COVID pandemic), and optimising a new private venture plankton modelling platform (DRAMA) for PML deployments. The last mentioned is being applied to a project on Lake Erie (USA) and also on the harmful algal species Prymnesium, which is a major fish-killing species in low salinity waters.”

The plankton modelling platform DRAMA (Dynamic Resource Acquisition Modulated Activity) outlines an enhanced modelling structure to more accurately simulate plankton behaviour. Professor Flynn describes its origin.

“I have long harboured an aspiration to build a suite of plankton models that enable the user to configure each as one would players in a computer game, and then to enact scenarios. This, together with a natural progression through building a decision support tool for microalgal biomass production, led to our development of DRAMA as a platform for what in current parlance, is intended to provide a digital twin. A digital twin, to my mind, provides a dynamic in silico replication of reality; think flight simulator! As a laboratory worker, my original aspiration was to design a test bed for such a digital twin as both a decision support tool in experiment design, and also as a means to better exploit the emergent knowledge.”

“Developing this further, digital twins of more complex systems could provide management platforms for aquaculture, coastal and other ecosystems. Ultimately, logic would see plankton digital twins replacing the very simple descriptions in extant models, descriptions that Mike Fasham already recognised as far from ideal back in 2000. With this in mind, and supported by NERC, over the last few years I have worked with 30+ plankton experts (from viruses to krill) on establishing what a plankton digital twin platform would look like. Prototypes exist, but funding is needed to progress this further.”

“Why are these digital twins needed? Well, simulation models uniquely enable us to bring all of our knowledge together. If you cannot model the plankton satisfactorily, you do not have sufficient information so you cannot claim to understand it fully. If you can tick those boxes, then you can move forward with some level of confidence. Prediction, extrapolation beyond the known, can only ever be as robust as the extant knowledge base underpinning the models. Modelling thus needs to become as routine a tool for plankton research as any other tool. That takes convincing people to invest in time and effort, and also critically that we even need to go there. There are sectors that believe that we do not, that the job is done well enough already. Others of us seek to argue differently; that we are indeed not done is evidenced by the mixoplankton paradigm.” The latest on these arguments was published in 2025.

Professor Flynn, whilst busy enough with such projects, has also been instrumental in the development of the first-ever Plankton Manifesto, a groundbreaking and landmark document launched at the 79th session of the United Nations General Assembly.

He was a part of the core editorial team, whose work in this document emphasises the critical importance of plankton in addressing the interlinked global crises of climate change, pollution, and biodiversity loss. He describes his work on the Plankton Manifesto, and reflects on how it might shape the future for generations to come.

“The Manifesto occupied a vast amount of largely private time over the last year (no space on the timesheet for that and I, nominally, work part-time!). In total, PML (I) contributed very significantly to the project; the glossary, for example, remains as almost a total PML text block. It was at times, however, a greatly frustrating activity, trying to get experts on different facets of plankton and microalgal biotechnology to sort of agree on what should be in or out on what had to be a compact document. Much text, and thence much time, was just cut out at one stage.”

“From a personal perspective, I was pleased to see that ‘mixoplankton’ are well represented, that at least the younger generation will see this term and understand why oceanic plankton do not function according to the traditionally argued plant-animal (phytoplankton-zooplankton) dichotomy. The whole project was also a salutary reminder that we teach our children almost nothing about the organisms that shaped Earth and that inhabit two-thirds of the planet. The word ‘protist’ (which for plankton includes all the non-cyanobacterial phytoplankton and mixoplankton, plus ca.60% of zooplankton) does not even appear in the school curriculum except in very brief reference to a few human parasites. On the flip side, during the drafting of the Manifesto, we also had to contend with some of the wilder ideas for mitigating climate change, such as by sowing the oceans with GM microalgae.”

Indeed, the Plankton Manifesto highlights the essential functions of plankton, which have been the foundational to life on Earth for over 3.5 billion years. These organisms, most of which are single-celled microbes, generated a significant portion of the world’s atmospheric oxygen while absorbing vast amounts of CO2, and continue to form the base of most marine food webs supporting fisheries worldwide.

Kevin is also currently working on iron (re)fertilization of the oceans, looking at ways in which plankton communities under climate change are affected by the availability if the vital micro-nutrient iron – see: Outdated models, changing oceans: a new look at iron and plankton · Oceanry.

“This work aligns well with my interests in how plankton communities are evolving and deployment of digital twins as tools for research and public engagement.”

Kevin continues on the topic of science and ocean literacy:

“Of increasing interest to me is the whole water/ocean literacy topic, for which gamification via modelling provides a route to engage with students of all ages in topics that are otherwise closed or of no immediate interest to them. A rewrite of my introduction to dynamic ecology textbook is on the cards as part of this.”

Kevin also works on the ProBleu project, to promote ocean and water literacy in school communities. ProBleu have launched free ocean literacy materials for schools across Europe, find out more here >>

To round up the interview, we asked Kevin whether he could tell us about any highlights or special moments from your career.

“If I have to identify a single thing it is actually a sense that my interests and expertise may actually be appreciated at PML. When others heard of my moving to PML, the response was either along the lines of, ‘about time too’, or from folk in certain institutes ‘you should have moved to us!’. Both rather flag that the decision of PML management to take me on was good for me; I cannot comment on whether the converse view is held, of course.”

Our last question for Kevin was to find out a little more about who he is outside of work, and what he likes to do to unwind after a busy day in the office.

“My hobbies include making models (as in wooden model boats and aircraft), flying RC aircraft, helicopters and drones, kayaking, cycling, walking, and photography. We are lucky to live next to Britain’s first area of outstanding natural beauty (the Gower peninsula in S.Wales), but rather unlucky in that the formally 3 hr drive to Plymouth now takes more like 4.5 hrs thanks to the increasing transport challenges. WhatsApp allows me to feel part of the PML modelling team beyond work, so I guess I should rightly add that WhatsApp group to the hobbies list as well.”

Image caption: Kayaking through the North Gower salt marshes at high tide. Kevin is in the back of the double kayak, flying the drone. He said, ”Landing the drone in your hand when seated in a drifting kayak is something of an art which is very painful if you fail and the rotor blades clip your fingers!”

Image caption: Kevin snorkeling off Thailand (2024), nominally looking for green Noctiluca! ”Actually, we were there teaching plankton modelling and for a workshop on mixoplankton.”

Related information

ResearchGate profile: Professor Kevin J Flynn

Latest papers and news from Prof Flynn:

Photosynthesis on a schedule: how can planktonic microalgae physiology remain active after dark?

Harnessing plankton research to inform next generation climate models

Think you know your mixoplankton from your phytoplankton?

MEDIA: How Does Life Happen When There’s Barely Any Light?

PML scientists contribute to groundbreaking Plankton Manifesto

Project ProBleu: Promoting ocean and water literacy in school communities

PML’s ocean acidification work shortlisted for the 2023 NERC Impact Awards

International scientists to gather for major air-water gas exchange summit