Story

How bubbles may speed up CO2 uptake by the ocean

16 December 2025

New study provides evidence that the ocean may have absorbed as much as 15% (0.3-0.4 Pg C yr-1) more CO2 than previously thought, requiring a re-think of future CO2 flux assessments and global climate models.

Dramatic waves of the Atlantic Ocean taken during a research expedition. Dr Ming-Xi Yang

The exchange of carbon dioxide (CO2) between the sea and air is a significant part of the global carbon cycle and plays a critical role in buffering climate change.

As the ocean is a major absorber of CO2, accurate quantification of this sea-air CO2 flux is vital for forecasting the future climate and developing effective climate change mitigation strategies.

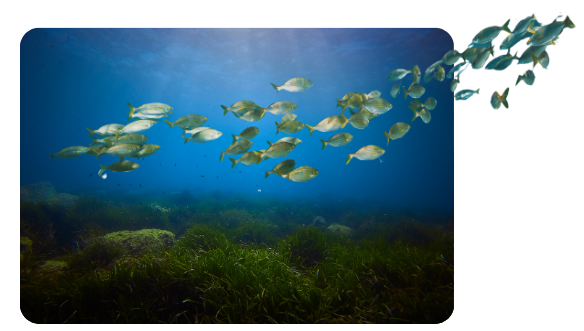

Sea-air CO2 fluxes vary regionally and seasonally between uptake and outgassing, meaning that in some areas the ocean is absorbing CO2 and in other areas, releasing it. In turbulent areas where there is more wave action, uptake is generally more due to bubbles of air getting engulfed by waves that enables the seawater to ‘absorb’ the gas trapped within the bubble.

Traditionally, sea-air CO₂ fluxes have been calculated using a blanket ‘symmetric’ equation that assumes the rate of gas transfer is dependent on the difference in CO₂ concentration between the seawater and air, and regardless if the CO₂ is being taken up or outgassed.

In recent years questions have been raised on whether an ‘asymmetric bubble effect’ had been overlooked since submerged bubbles that are under pressure favour CO₂ flux uptake over outgassing. However, this hypothesis lacked suitable evidence until now.

In this first-of-its-kind study, led by Plymouth Marine Laboratory and GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research (Germany) with a partner from Heriot-Watt University, 4,082 hours of high-quality sea-air CO₂ flux measurements, collected over 17 ship cruises and covering a variety of ocean regions, were re-analysed to investigate if bubble-mediated transfer acts in a more asymmetric manner.

Using a novel ‘2-dimensional’ fitting method, the analysis shows clear field evidence of asymmetric bubble-mediated CO₂ in the ship observations. When the team recalculated global sea-air CO₂ fluxes (for 1991–2020) using the asymmetric formulation, they found that the global ocean’s CO₂ uptake increased by about 15% (0.3-0.4 Pg C yr-1) compared with conventional, symmetric estimates.

The asymmetric increase in CO₂ uptake is especially strong in regions with frequent high winds and wave breaking, such as in the Southern Ocean where some of the stronger climate change impacts are already being seen.

These results suggest that the global ocean may have been absorbing more human-produced CO₂ than previously thought, thereby further buffering climate change. This has major implications for the understanding of the global carbon budget and climate change mitigation.

Lead author, Dr Yuanxu Dong, previously a PhD student associated with Plymouth Marine Laboratory and now a Humboldt fellowship postdoc at GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research and Heidelberg University in Germany, commented:

“This study challenges standard assumptions of the symmetric flux formula used in many carbon cycle and climate models. This means that many past estimates may be systematically biased and we urge that future CO₂ flux assessments should adopt the asymmetric formula”.

Dr Ming-Xi Yang, co-author and Chemical Oceanographer at Plymouth Marine Laboratory, added:

“Accounting for the asymmetry means that the ocean CO2 flux estimates diverge even more between what is computed from observations and what is estimated from global models. This suggests that there may be shortcomings in the global models and of course, we need those models to be as realistic as possible to make accurate future CO2 and climate projections”.

The study team note that more outgassing measurements are needed, especially under high-wind/wave conditions that are more challenging to obtain.