Story

New evidence reveals how Greenland’s seaweed locks away carbon in the deep ocean

23 January 2026

An interdisciplinary study confirms, for the first time, the oceanographic pathways that transport floating macroalgae from the coastal waters of Southwest Greenland to deep-sea carbon reservoirs, potentially playing a previously underappreciated role in global carbon storage.

Greenland’s rocky shore. Mathilde Cureau | Unsplash

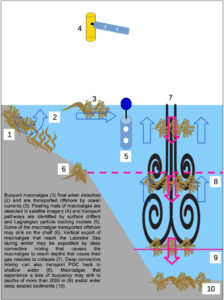

Macroalgae, or seaweeds (including kelp), are highly productive coastal habitats capable of absorbing significant quantities of atmospheric carbon (CO₂). Previous studies have estimated that globally, 4–44 teragrams (1Tg = one million metric tonnes) per year of macroalgal-derived carbon may reach depths of 200m, where it may be sequestered for at least 100 years.

However, macroalgae’s contribution to long-term carbon storage has been challenging to quantify with any certainty due to issues including: the wide range of macroalgae properties that need to be considered; the complexity of interactions with physical oceanographic transport processes, and a lack of scientific evidence about the travels and transformations of detached macroalgae after leaving coastal rocky shores.

To address this knowledge gap, the study team, co-led by the Leibniz Institute for Baltic Sea Research Warnemünde and Helmholtz-Zentrum Hereon in Germany and involving scientists from Plymouth Marine Laboratory, University of Exeter, Portugal, Saudi Arabia and Denmark, used a combination of satellite imagery, ocean drifter tracking, numerical modelling and advanced turbulence analyses to demonstrate that extensive mats of macroalgae can travel hundreds of kilometres offshore. Eventually these mats may sink to great depths where their organic carbon may be stored long-term.

Data from 305 oceanographic monitoring devices, that float on the surface to investigate ocean currents by tracking their location, and numerical simulation models showed that ocean currents can carry buoyant macroalgae from coastal zones into deeper waters on ecological timescales (averaging 12–64 days), often before structural breakdown occurs.

![[A] The trajectories of 30 Hereon drifters in the Labrador Sea. Drifters were deployed in late August 2022 and recorded their positions for ∼75 days. [B] Drifters were initially entrained into mesoscale eddies, where they remained for the first 24 days. [C] After leaving the eddies, the drifters were transported to the southeast, while also exhibiting looping behaviors. Black ‘X'-s and red circles denote starting and ending points, respectively, of the trajectories considered.](https://pml.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/1-s2.0-S004896972502889X-gr6_lrg-182x300.jpg)

![[A] Locations of floating mats of macroalgae color-coded by month. Also shown are the combined footprints of the Sentinel-2 tiles and the 1000m isobath (dashed black line). Floating algae index [B] and true color [C] Sentinel-2 image from 19 August 2020 showing the largest individual mat of floating macroalgae detected with an area of 221,900 m2. The inset in [B] shows the location of the mat.](https://pml.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/1-s2.0-S004896972502889X-gr3_lrg-1024x341.jpg)

Lead author, Dr Daniel Carlson from the Leibniz Institute for Baltic Sea Research Warnemünde, commented about the study:

“Our study highlights not only the importance of macroalgae in the ocean carbon cycle, but also the critical role of international scientific collaboration and support for long-term, open-access datasets. Observational assessments of macroalgal transport in remote and challenging locations, like the SW Greenland shelf and the Labrador Sea, were only possible because of Sentinel-2 satellite imagery provided by Europe’s Copernicus programme and data from the Global Drifter Program maintained by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Continued support for these datasets, and others like them, will help to empower a border-less scientific community – which in our case included scientists from institutions in 8 countries – to unite in solving planetary-scale problems that are too vast for any one nation to tackle alone.”

Prof. Ana Queirós, Marine Climate Change Ecologist and Climate Change lead at Plymouth Marine Laboratory, added:

“This study in another smoking gun providing evidence that seaweed carbon is likely ending up in deep sea sinks, by identifying the physical ocean processes that connect near-shore production with deep-ocean carbon sequestration;.”

“Our findings illustrate a tangible oceanic conveyor belt that links thriving coastal macroalgal forests with the deep ocean’s carbon reservoir. Recognising these natural transport and mixing pathways enhances how we understand macroalgae’s vital role in the Earth’s carbon cycle.”

“These so called “carbon sinks” are natural routes in the ocean that lock carbon away from the atmosphere, where human-driven excess carbon dioxide emissions are warming our planet. This study therefore reinforces the view that seaweeds make an important contribution to the regulations of our climate system.”

Southwest Greenland was selected as the case study area as it provides an ideal location to test the assumptions underlying estimates of macroalgal export from coastal areas to the deep sea.

The area has abundant macroalgae on its rocky coastline, the dominant species of brown algae float when detached, and other studies have confirmed that sediment eDNA identified macroalgae in sediment extending from shallow nearshore areas to 1460m depth and 350 km offshore.

The prevalence of macroalgae in Greenland and Arctic shelf, slope and deep-sea sediments, with a dominance of brown algae, has been maintained for millennia, documenting that macroalgae export from Greenland contribute to long-term carbon burial in the Arctic.

For future studies the team recommends a large-scale interdisciplinary study to observe the three primary processes that result in export of floating macroalgae from coastal sources to potential sinks in the Labrador Sea: 1) detachment; 2) offshore export by surface currents; 3) vertical export.

To achieve this, observations of floating longevities and rising velocities of the dominant floating macroalgae species must be determined experimentally, as well as their sinking velocities after the buoyancy structures collapse. Similarly, the depth at which the buoyancy structures collapse occurs must be determined to develop reliable parameterizations for vertical export.

Overall, the study determines that protecting and restoring coastal macroalgal forests around the world may have significant climate benefits that extend far beyond the shoreline, reinforcing the need to protect deep sea ecosystems receiving that carbon, and the role of both areas in regulating our planet’s climate.

Related information