Story

Why is sargassum seaweed swamping West African coasts?

08 October 2025

In recent years, huge blooms of Sargassum seaweed have appeared across the Tropical Atlantic, piling up on coasts in the Caribbean, Gulf of Mexico… and increasingly West Africa – causing mayhem for coastal communities as they face major environmental and socio-economic impacts from this drifting seaweed.

Image caption: Sargassum chokes a popular fishing beach in Barbados. Since about 2011, huge swathes of sargassum have been washing ashore in more than 30 countries in the Tropical Atlantic.

While most Sargassum species attach to the seafloor, two exceptional species – Sargassum natans and Sargassum fluitans – are entirely pelagic. They float freely at the surface of the Ocean, kept buoyant by small air-filled grape-like sacs called pneumatocysts, which lift them for photosynthesis.

Image: Sargassum fluitans up close, pictured in Ghana. Image credit: Dr Yanna Alexia Fidai.

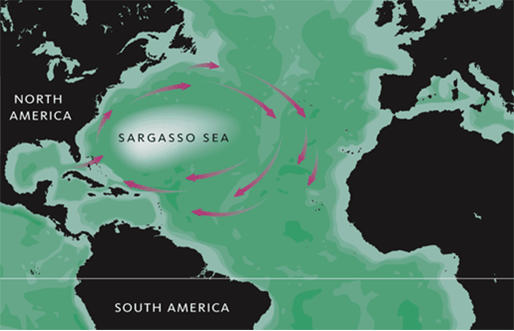

These two species in particular are native to the tropical and subtropical Atlantic Ocean, particularly the Sargasso Sea region.

Image: The Sargasso Sea is a region of the Atlantic Ocean bounded by four currents, forming an ocean gyre. It is the only named sea without land boundaries. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

The Sargasso Sea in the North Atlantic was actually named after these seaweeds, due to the large floating mats that characterise the region, and their name is thought to have originated either from ‘early Portuguese sailors who compared the weed and its air-filled clusters of bladders to grapes, or from the Spanish word “sargazzo” meaning kelp.’ [Source: Sargasso Sea Commission]

In recent years, however, these mats of Sargassum have proliferated, and massive blooms have been appearing across the tropical Atlantic, the Caribbean, and the West African coast, forming what scientists call the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt.

Mats can reach depths of up to 7 metres and can span hundreds of kilometres, with thousands of tons washing ashore each year.

The impacts of these blooms are far-reaching. In coastal waters, dense mats of Sargassum can smother coral reefs and seagrass, blocking sunlight and oxygen while driving eutrophication – the process where water bodies become over-enriched with nutrients, particularly nitrogen and phosphorus – as they decompose.

On land, when washed ashore, decaying seaweed releases toxic gases such as hydrogen sulfide and ammonia, posing health risks and contaminating groundwater. Communities across the Caribbean and West Africa are also facing economic hardship, as the seaweed clogs fishing gear, damages boat engines, and deters tourists with its strong odour and unsightly build-up. What was once a vital ocean habitat has now become a transboundary challenge for ecosystems, public health, and coastal livelihoods alike.

These unprecedented accumulations in recent times are thought to have been fuelled by a combination of climate change, nutrient pollution, and shifting ocean–atmosphere patterns such as the North Atlantic Oscillation.

However, most scientific studies have focused on areas such as the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico. West Africa remains underrepresented in global Sargassum research, with limited studies exploring how seasonal and annual patterns vary across the region, and a lack of consensus exists on seasonal and annual trends. Meanwhile, its coastal communities have been grappling with the consequences of these blooms, but lack the benefit of long-term data and forecasting tools.

Image caption: In Ghana, Sargassum blooms have been shown to disrupt coastal livelihoods, as the seaweed becomes entangled in fishing nets, reducing catches and damaging equipment. When it washes ashore, it also affects the appearance and smell of beaches, creating further challenges for local communities. These impacts have real socio-economic consequences, with some residents resorting to food or fish rationing, taking out loans, wearing masks to cope with the odour, or seeking alternative sources of income. Image credit: Dr Yanna Alexia Fidai.

A new study led by Dr Yanna Alexia Fidai of Plymouth Marine Laboratory (PML) provides the first attempt to characterise the seasonal and annual patterns of sargassum biomass in West Africa and the Eastern Tropical Atlantic.

Using over a decade of satellite observations (2011–2022), the research identifies clear trends, with biomass typically peaking in September in northern regions (Guinea to Gabon) and in July–August further south (Gabon to Angola), alongside smaller secondary peaks.

Beyond identifying when and where blooms are most likely to occur, Dr Fidai’s study also explores the possible drivers of sargassum movement and proliferation in the region. While sea surface temperature emerged as one important factor, the findings suggest there is no single driver. Instead, a combination of oceanic, atmospheric, and potentially human-driven processes are likely working together to fuel these events.

“We theorise that there isn’t one dominant cause of sargassum blooms in West Africa, but a set of compounding factors that interact in complex ways,” said Dr Fidai. “By better understanding these patterns and processes, we can help communities anticipate, prepare for, and manage the impacts of future events.”

This work is a crucial step toward improving monitoring and forecasting for West Africa, where communities are not only facing the ecological and socio-economic costs of sargassum influxes, but also exploring opportunities to use the seaweed for fertiliser, biofuel, animal feed and more.

However, the study also highlights major data challenges, especially cloud cover in the intertropical convergence zone, which hampers satellite detection. Overcoming these gaps will be essential for advancing reliable prediction systems and helping governments, industries, and communities adapt.

By offering the first comprehensive view of sargassum seasonality in the Eastern Tropical Atlantic, this research provides a foundation for future studies – and a vital resource for those living and working along affected coastlines.